By Jenny Watters

In The News Again

North Korea Crisis Rekindles Memories

of Military Service

The international stand-off between the United States and North

Korea over the latter’s renegade nuclear weapons program has reawakened

memories of an all-but-forgotten chapter of U.S. history.

In 1950, the United States sent hundreds of thousands of troops to defend the southern peninsula of Korea against invading North Korean communists. Initially described as a “police action,” the conflict settled into a long and bloody stalemate. More than 54,000 Americans were killed during the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, nearly as many as were lost in Vietnam. As during World War II and Vietnam, students from Walla Walla College served their country with distinction. Half a century removed from the war, several alumni and wwc professors belonging to this forgotten generation of veterans remember the Korean War as a time of challenges to themselves and to their nation.

“Anyone who says that isn’t nerve-racking or stressful is kidding themselves. Even as quiet as I had it,” says Marion Hanson, who attended wwc in 1953. Drafted in 1951, Hanson accepted the inevitable: “If it has to be, it has to be. You defend your country.”

Trained as a medic, Hanson spent about three months of his tour on the front lines. He recalls waiting at the end of a road for mail call. “I was talking to another guy when this whistle went between us. We both hit the ground before our helmets did. He said, ‘That was right behind your head;’ I said, ‘It was behind yours,’ so we decided it was between us.”

Hanson went on night patrols in No Man’s Land. By starlight they traveled on 16-inch terraced rice patty trails. “You could smell garlic like you wouldn’t believe—the North Koreans ate garlic.

I don’t know how many there were, but they didn’t feel brave enough to take us on.” Still not out of harm’s way, Hanson and his shipmates faced a severe typhoon on their way home.

Historian

Robert Weisbrot observes that the Korean War “was a mess without any

clear result—there was no clear resolution. There were only countries

that suffered, but none that officially lost.” For Hanson the outcome

was disappointing.

Historian

Robert Weisbrot observes that the Korean War “was a mess without any

clear result—there was no clear resolution. There were only countries

that suffered, but none that officially lost.” For Hanson the outcome

was disappointing.

“I really think if they’d left MacArthur alone we would have had a united Korea. We wouldn’t have a nuclear North Korea like we do now. At times I think we’re forgotten. You seldom, if ever, hear about Korean War veterans. I don’t let myself be bitter. It’s one of those things.”

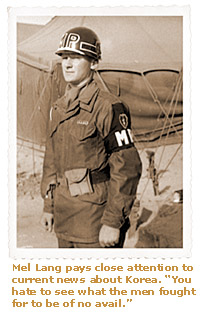

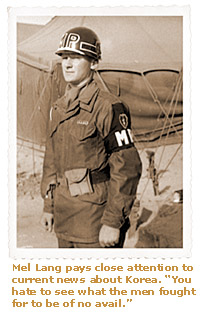

Former wwc mathematics professor and college administrator Mel Lang was drafted in 1952 and went to Korea in 1954. “I went as an infantryman, and volunteered for the mp [military police]. I decided that would be better than sleeping in a pup tent.” Lang was not a church member at the time, so he didn’t claim conscientious objector status. As with many young men at the time, Lang says, “I felt this is what I had to do to pay my dues to live in this country. The idea of killing is something that you kind of accept, which is strange as you look back on it, but at that time it didn’t seem that strange. The cause was right.”

Within a month of returning home, Lang was back in college.

“In the service, you have hours to think. In some sense it helped me

figure things out. You grow up very fast in the service. If you can come through

it without too many scars, you learn discipline.”

Lang says he pays close attention to news about Korea. “When I hear that

the tension has increased, I hate to see what the men fought for to be of

no avail.”

Dale Brusett, a 1960 graduate, enlisted in 1951 so his brother

who had been drafted would not have to go into the service. His mother was

Seventh-day Adventist and he had attended Mt. Ellis Academy, but he was not

a church member. Brusett was stationed near the front lines in an area called

“The Hook.” A dedicated soldier, he became platoon leader. On a

night patrol Brusett’s platoon was ambushed, and his close friend was

shot and killed. Soon after, a grenade landed near Brusett himself. He hit

the ground. “I felt this was it and called out to God, ‘If you get

me out of this alive I’ll serve you the rest of my life.’”

The grenade exploded and burned Brusett’s face. He realized he was alive

and picked up his friend to carry him back. Brusett received the Purple Heart

for his bravery.

Brusett says he forgot about the promise he made to God. Back home he was injured in a tractor accident. At the va hospital he met some Seventh-day Adventists who invited him to church, and his mother encouraged him to enroll at wwc. “I was still smoking—had a hard time giving that up,” Brusett recalls. Eventually baptized by Paul Heubach, Brusett majored in theology. He pastored in Montana and traveled widely as an evangelist. “The promise I made to God changed my life.”

Brusett holds no bitterness about the war, but acknowledges that he and other soldiers were upset when Truman got rid of MacArthur. “We wanted to finish what we came over there for; we were ready and we knew the risk. If we had been allowed to carry out the mission there would be a united Korea,” he says.

Loren Dickinson, former communications professor, was drafted into the army his junior year at Union College, a Seventh-day Adventist college in Lincoln, Neb. As a conscientious objector he was trained as a medic. He recalls finding the “arbitrary military style” to be difficult to deal with. Dickinson was assigned to a medical battalion south of the DMZ (de-militarized zone) and became involved in Troop Information and Education. He ran the battalion newspaper, served as librarian, and tutored soldiers who had not completed eighth grade. The fighting ceased several months before he arrived in Korea.

Of his time in the military Dickinson observes, ‘I developed a strong feel for how undesirable it is to live under authoritarian, arbitrary systems. I think I was far less arbitrary and more sympathetic as a teacher than I might have been if I hadn’t gone through that.” He continues, “The experience was a maturing one for me. One of my vows when I went over there was to try to stand out as one who could be trusted, one who was good for his word. Maybe even lead someone to think about how I led my life—I wasn’t drinking, smoking, and carousing. I actively thought about it and actively tried to live it.”

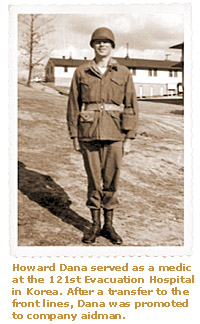

Howard

Dana, who attended wwc in 1953, was threatened with court martial by a captain

at Ft. Mead, Md., when he wouldn’t work kp (kitchen patrol) on Sabbath.

Miraculously, Dana says, the issue was suddenly dropped. He carried Steps

to Christ with him on his medic duties at the 121st Evacuation Hospital in

Korea. Dana was transferred to the front lines and was promoted to company

aidman where he was involved in patrols and firefights. On one occasion he

and another company aidman had to pick shrapnel out of each other’s backs.

“I was shot at several times but never hit. I prayed all the time,”

he recalls. A fellow medic “was cracking up—the combat got to him.”

Howard

Dana, who attended wwc in 1953, was threatened with court martial by a captain

at Ft. Mead, Md., when he wouldn’t work kp (kitchen patrol) on Sabbath.

Miraculously, Dana says, the issue was suddenly dropped. He carried Steps

to Christ with him on his medic duties at the 121st Evacuation Hospital in

Korea. Dana was transferred to the front lines and was promoted to company

aidman where he was involved in patrols and firefights. On one occasion he

and another company aidman had to pick shrapnel out of each other’s backs.

“I was shot at several times but never hit. I prayed all the time,”

he recalls. A fellow medic “was cracking up—the combat got to him.”

Dana’s faith in God was his source of strength. “He took care of me. The experience in Korea has given me a better trust in God.”

Jenny Watters lives in Portland, Ore. She graduated from wwc in 1985 with majors in journalism and social work.