Alumni Gazzette

A Genuine Class Act

By Amy Wilkinson

At an age when most boys daydream of becoming firefighters or police officers, 13-year-old David Vixie was busy dreaming up curriculum he would use in his future career as a teacher. Almost 40 years later, David, a 1977 elementary education and 1983 master of education graduate, was selected from 50,000 nominees to receive the Disney Teacher of the Year Award for his innovative teaching style. Whether in the classroom or on the trail, the Paradise Adventist Academy teacher treats his students to adventures they will never forget.

|

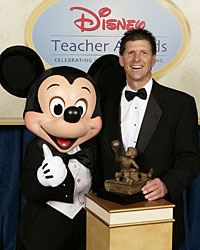

| Eighth-grade teacher David Vixie receives a Mouscar for his innovative teaching style. |

Who or what influenced your decision to

go into teaching?

A seventh-grade health assignment asked me to show and tell what I would be

when I was grown. I selected a picture of a bald, middle-aged man dressed

in black and white and said I would be a teacher. It must have been a serious

commitment to teaching for a teenage boy to be willing to accept that common

image.

What subjects do you teach?

I teach all subjects in a self-contained eighth-grade classroom. Most junior

high classrooms are departmentalized, but I have an unusual blessing. In this

setting I have a greater opportunity to teach life values and skills. People

don’t live their lives departmentalized into subject segments. Though

we may spend extended time solving math-related issues or reading a good book,

we generally access subjects throughout the day, intermingling relevant portions,

as the needs demand. That is how I teach.

You received the Teacher of the Year Award

for your creativity and innovation in the classroom. What are some things

you do to add creativity to the learning process?

I teach using metaphors and simulations that bring students into a relevant

curriculum that challenges them to go beyond whatever level they are at.

For example, to study the overland migration of the mid-19th century, we learn to manage horses, rebuild and maintain old covered wagons, and travel for many days and miles along the California Overland Trail behind teams of mules.

Students read diaries of people who described packing their wagons and making daily social, natural, and scientific observations. These emigrants noted the ecology, calculated distances and speed, explored human interactions, and wrote personal narratives of their travels and they did so without getting a grade for it. They believed what they were doing mattered.

The students find themselves involved naturally in these same human behaviors while on the trail. They write journals of their own with emotional commitment. They make observations, solve similar problems, and discover the success of the journey comes from looking after the needs of others.

Back in the classroom, the wagon and its many artifacts supplement academic instruction.

But this event is more than just about a neat ride down a historic trail or a cute classroom display. These are events for exploring character and testing values. Students can gain hope from knowing a lot of the beauty in this world has come from a lot of pain.

Teachers are supposed to teach, but sometimes

they also learn from their students. Do any instances stand out in your mind

when you were “taught” a truth by one of your students?

It was my first week of teaching. I caught a student cheating. I ripped his

paper in half in front of all his classmates. They were aghast. The boy who

had cheated looked ashamed and embarrassed. At first I thought, “Good,

you deserve it; no one will dare cheat now.” Then I realized I had created

fear in the classroom. That was the reason the students would behave. Fear

is the lowest level of motivation. The highest level is love. I called my

father for advice. He said, “You can’t make your students love you.

You can’t make them do anything. But you can give them a reason to respect

you. You will do that by treating them with respect and dignity.”

How can parents encourage a love of learning

in their children?

First, show respect and dignity when interacting with your child’s teachers

and friends. Second, give your child many real experiences through museums,

travel, adventures, and decision-making scenarios. These experiences will

provide hooks that teachers can hang lessons onto with meaning. Third, model

being a learner yourself. Instead of asking “What did you learn in school

today?” say, “Guess what I learned today.”

|

| David doesn’t just lecture about the Overland Trail, he and his students retrace its path in their own covered wagon and old-fashioned garb. |

Who was your most influential teacher?

My most influential teachers were the ones who provided insight when I was

ready for it rather than when it was convenient for them. Sometimes that was

a dog or a horse, other times it was a personal experience, mistake, or influential

person.

Omer Luke, a rancher in Milton-Freewater, Ore., taught me to train horses

without force or fear. I watched for clues that the horse was ready to learn.

I learned to observe and to understand the role of the trainer and the learner.

Carolyn Hazelton in the education department of WWC taught me

to put educational theories into creative practice. A visiting philosophy

professor assigned me to be still and think and value my thoughts.

Tell us about your week at the Disneyland

Resort in California.

We were picked up at the airport in a chauffeured town car. I looked out the

tinted windows, and thinking of the incredible wages of some actors and sports

stars, I said ‘So this is what it feels like to be an overpaid teacher!’

We spent one afternoon getting acquainted with all the 45 Disney American Teachers and attending a professional development session given by the Institute of Collaborative Education from Boston, Mass. In October we spent an entire week in professional development together in Orlando, Fla.

What an incredible experience it was to listen to 44 other amazing, creative educators ranging from only several to 47 years of experience as they shared their heart of teaching. I sat on the edge of my seat realizing I was blessed with a special showing of what is represented in America’s teachers through innovation, creativity, and inspiration.

The big event, the gala, was modeled after the Oscars with our trophies referred to as “Mouscars.” We were fitted in evening gowns and tuxedos, which elicited the tremendous compliment “You look nice,” from my mother. We sat at tables and enjoyed the music, pictures, and our evening host, actor Hector Elizondo. A special guest appearance by 93-year-old Art Linkletter and his dialogue from Kids Say the Darndest Things were both inspiring and entertaining. Each teacher was celebrated for the leading roles they play in the lives they touch. Special awards were given for service, meeting special needs, and Teachers of the Year for elementary, middle school, high school, and educational specialists.

What was it like to hear that you were

chosen for not one, but two awards?

You do not have to be a category winner to be selected as Teacher of the Year.

In fact, they said it is uncommon to receive more than one award. So when

I was announced as Middle School Teacher of the Year I felt truly honored

to have been selected in the category of my expertise. On my way back to my

seat I slipped past my daughter’s table and received her congratulations.

I told her to relax now because I would only be getting one award. So when

my name was called for Teacher of the Year it was an amazing surprise. I kissed

my wife to the tune “Can You Feel the Love Tonight,” then went forward

to receive the award.