By Marlan Kay

Beyond the Lecture

Fleeing the Classroom

The classroom is a beach or a hostel lobby. A coffee shop or a boat in the middle of the ocean. Students sit on couches and jot notes while sipping hot chocolate. Or they might walk through an open field as they listen to their instructor—who is dressed in shorts and sandals. Welcome to class.

Many college students today are leaving campus to have class. For them, the classroom is often not comfortable enough, not close enough to the material they are studying. So instead of trying to bring the subject into the classroom, the classroom is brought to the subject.

Many teachers take advantage of long class periods, weekends, and summer or spring breaks to take students away from desks and chalkboards. These classes are unique, and because of this, they are classes students often love, talk about, and line up on waiting lists to get into.

But how useful is it to leave campus to have class? Does it really help students learn, or is it just a ploy to get them interested? Should teachers try to spark students’ enthusiasm by bringing them away from the classroom?

The Big Trips. Posted on the wall outside Jim Nestler’s door are photos. Lots of photos. Depending on the month or year, the pictures may be of Hawaii, the Washington coast, or the Arizona desert. Nestler, a professor of biology and the director of Walla Walla College’s marine station, typically teaches special biology classes over spring break every year. In these classes, he takes students—less than 15 at a time—away from campus. Far away.

Instead of studying desert biology in a classroom, he takes the students to Arizona to study it up close. Instead of looking at tropical biology textbooks in the distinctly non-tropical College Place, he takes them to Hawaii. Why? Nestler says it helps students relate much more easily to material that they might only read about in the classroom.

“We see pretty pictures, read descriptions, hear things on the news about different places, but until you actually see things yourself, pick things up and touch them yourself, you can’t really understand it,” he asserts. “You really learn when you’re hands-on with what you’re studying. One thing this department is big on is getting students’ hands dirty.”

The entire focus of biology, after all, is to study life—plant life, animal life, and all that goes with it; it makes very little sense to talk about life in theory, but never see it up close.

But biology isn’t the only subject that is advantageous

to study up close and personal. Even literary subjects can lend themselves

to getting away from campus to a new location. Carolyn Shultz, professor of

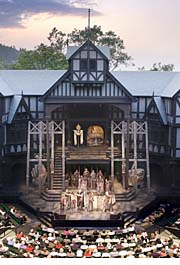

English, teaches a weeklong course each summer in Ashland, Ore.

The subject? Shakespearean plays. The classrooms? A hostel lobby and a theater.

The object? To study Shakespeare as more than just literature, but as a performing

art.

Why?

Shultz says that’s what Shakespeare is supposed to be all

about.

“Just sitting and reading it is one thing. Seeing it is better,”

she says. “I could take Shakespeare like that all the time, because you

need to see it live. It’s the ideal way.”

And what better place is there to see Shakespeare live than at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, where America’s oldest Shakespeare company performs each summer? There, students can not only see the plays, but also see the backstage operations, talk to actors, and have class—all at the same time.

This appreciation of on-location learning is echoed in many other departments. Terrie Aamodt sometimes takes history students on Civil War tours, traveling to battlefields and other places where history was made.

Aamodt says that the kinesthetic aspect of the tours really brings the material close to the students. When they hike across the terrain and walk around on the battlefields, they see and experience the history. It becomes real to them.

But despite the ability to see material up close, are students really learning as much off campus? Sure, the new environment helps bump up student enthusiasm, but don’t these kinds of classes put fun in the place of genuine, academic learning?

Nestler doesn’t think so. He says students sometimes come

into his classes thinking the trip will be a vacation, but he makes them work

hard. Before they even go, they are required to have a significant amount

of theoretical understanding of the material they’ll be studying.

“There needs to be a balance. You can’t just get thrown into a lab

or field experiment without knowing why you’re doing the things you’re

doing.”

Shultz students are no different. Over the course of the class, they participate in lots of discussion, write essays on every play they see, and finish the course with a longer paper.

But beyond tangible studying, students are often able to interact with the subject more openly on these trips because of the relaxed atmosphere. They see and talk with the professor in a brand new way. Once students know the professor and the material personally, they are uniquely engaged in the subject.

“Because it’s much more casual, the students are more comfortable, and if they’re more comfortable, they’re going to be able to actually learn much more easily,” Nestler says.

Not only does this casualness promote strong academic communication with other students and professors, but it also allows for other significant interaction. Nestler points out that most people don’t realize one of the most valuable aspects of large class trips.

“One thing I especially enjoy is seeing the spiritual side of trips like this,” he says. “The vast majority of students are extremely serious about their relationship with God, and it’s exciting to see. That’s something you just don’t always see in the classroom.”

On trips, people have more time to open up, and in an environment where most students and teachers are Christian, spiritual matter can become a common topic for discussion.

And when classes-by-the-hour are the rule of the day, it is difficult in many classes to integrate more than a short prayer or worship thought into an academic setting. Thus, the 24-hour spiritual interaction on these trips is extremely valuable to a Christian academic institution like Walla Walla College.

Closer to Home. Naturally, these large trips are special. They usually take place during extended breaks and finish within several weeks. Most quarter-long college courses don’t have that luxury.

At the same time, there are also ways many regular classes incorporate off-campus study into a regular syllabus. The Death and Dying class visits a funeral home each quarter. Classes in Modern Denominations require students to visit various churches. The Forensic Psychology class takes a tour of the state penitentiary. The class in Materials and Processes in Manufacturing visits fabrication and processing facilities. Scuba Diving and Ornithology classes go on weekend trips.

These jaunts bring students closer to the learning they are doing in the classroom. Even in small amounts, students get exposed to the real world, making the academic subjects seem real and applicable.

Of course, classes don’t need to go far off-campus to bring about hands-on learning. They can sometimes step right outside the classroom. One of the most useful methods of instruction, for instance, is often right down the hall—the laboratory.

Senior engineering major Angela Sugihara says that many of her engineering classes make good use of labs, and these labs get the students comfortable with the material. With lab experience, students become competent at applying academic material, and with that competence comes more confidence and interest in learning.

“Any exposure to what you’re studying about is good, because it makes it seem real,” she says, “You study it in class, and then you go out and see it. It reaffirms what you’ve already learned.”

She says this type of experience is often more useful than field trips, because in the lab students do things themselves, while field trips are often more about seeing or observing.

Now naturally, many liberal arts courses don’t have much use for a laboratory, but many of them can benefit from a more relaxed, discussion-oriented atmosphere, especially if they are small classes.

This is the reason that Aesthetics and Communication sometimes meets in a café and upper division French classes sometimes meet at a picnic table outside. The relaxed atmosphere helps students feel comfortable talking and discussing with the teacher.

So are off-campus classes and out-of-classroom instruction the key to all good learning? Certainly not. But they do offer some insight into what exactly does help students learn.

In the end, it’s all about learning, whatever the subject, wherever the location, and whatever the style of teaching. If the learning is effective, students leave college with academic knowledge, real-life experience, and a few extras that make them well-rounded individuals. W

Marlan Kay graduated in June with a major in communications. He is currently a freshman studying at the Loma Linda University School of Medicine.